By Jenni Vincent

The Journal

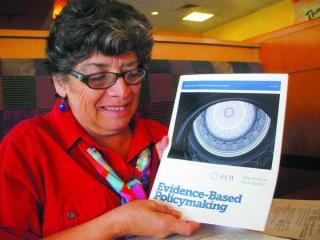

CHARLES TOWN, W.Va. — A self-proclaimed activist, Pauline Mejia is no stranger to spending lots of time – both professional and personal-working on behalf of others, including migrant workers, homeless individuals and heroin addicts.

And as a member of the West Virginia Advisory Committee to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Mejia once again found a way to reach out for a better tomorrow – especially recently, as she and other committee members appointed to this post began addressing their collective task.

As a result of intense study and discussion, they decided to focus on how the state’s criminal justice system deals with mentally-ill individuals – an effort that culminated with a public meeting held last month in Charleston, she said.

“We decided to focus on the experience of law enforcement with those experiencing a mental health crisis, because ultimately we wanted to have an understanding of how this system works. So back in about January, we started recruiting state experts to share with us,” Mejia said.

This day-long event, which featured four panel presentations as well as time for open discussion, also included a look at the West Virginia Mental Health Court’s current and projected capacity, said Mejia, who is now reaching the end of her two-year appointment and must reapply to serve another term.

Currently operating only in the Northern Panhandle’s First Judicial Circuit Court, which includes Hancock, Brooke and Ohio counties, the state Mental Health Court diverts non-violent criminal offenders, diagnosed with mental illness, from the criminal system into treatment, she said.

The good news is that after months of work, committee members assembled an outstanding group of experts – who represented various professional perspectives, including representatives from law enforcement, data analysis, drug court and mental hygiene commissioners – to speak as panel members on the subject, which Mejia termed “an especially time sensitive topic due to the growing concern about police shootings of mentally disabled people.”

That’s especially important because the Treatment Advocacy Center and the National Sheriff’s Association estimate that half of the number of people shot and killed by police have mental health disabilities, she said.

Despite the offerings, just a handful of people came to the sessions, but even that isn’t discouraging, she said, because committee members also had an opportunity to ask questions while trying to better understand the process, Mejia said.

“There is a lot of good news because this was a matter of fact-finding that helped establish a solid foundation, one that’s now in place and can help keep this discussion going,” she said.

“A paper is now being put together based on what we’ve discovered and our own research, one that will be submitted to state officials, including legislators, as well as federal Commission on Civil Rights,” Mejia said.

At that level, federal officials can see national trends, she said, adding, “When we were in our discovery phase of having experts talk to us about what’s happening nationwide, we also discovered there is a pattern concerning the response of first-line officers and people experiencing a mental health crisis – and that’s really the issue.”

And at the state level, issues remain to be addressed, including the need for a crisis intervention team – a team that includes a police officer and a behavioral health specialist to de-escalate a potential mental health situation – which was previously dismantled due to financial restraints, Mejia said.

It’s also telling, she said, that law enforcement trainees get four hours of training devoted to mental health during a 16-week curriculum.

While some individual departments do additional training, others don’t have the money or manpower for this expense, she said.

“The captain of the Huntington police force talked about having recently purchased a machine that provides more than 500 scenarios so that officers can learn how to respond, so that was interesting to hear about but is definitely the exception,” Mejia said.

Overall, it’s clear the needs currently out weigh available resources, Mejia said.

“One of the experts had been involved in the prison system in West Virginia, and he talked about how many of the guards didn’t have this kind of training – and that causes problems,” she said.

“Without exception, every single panel expert said there are not sufficient resources in terms of helping people with mental illness, whether you are talking about training, rehab or even behavioral health centers,” she said.

??

Staff writer Jenni Vincent can be reached at 304-263-8931, ext. 131, or twitter.com/jennivincentwv.