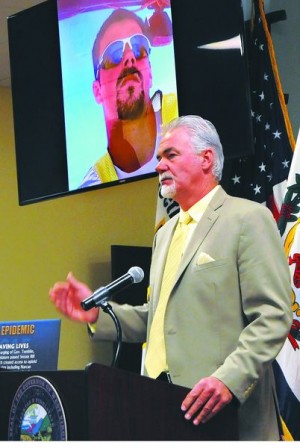

Berkeley County Council President Doug Copenhaver talks at the Governor’s Substance?Abuse Summit on Wednesday morning at the Berkeley County Sheriff’s Department in Martinsburg.

MARTINSBURG, W.Va. — Berkeley County Council President Doug Copenhaver and Martinsburg City Councilman Kevin Knowles shared their personal stories of addiction Wednesday, when they each described how substance abuse had literally been a matter of life and death for them.

While their experiences had some similarities, there was also a big difference – Knowles lived to fight and conquer his cocaine use and alcoholism, but Copenhaver instead described the pain of losing his son, who’d unsuccessfully battled his prescription pill addiction.

Although nearly 200 people were in the audience at Wednesday’s Governor’s Substance Abuse Summit when they spoke, there was total silence as Copenhaver -framed by photos of his late son, Douglas – appeared on two large screens beside him.

One showed Douglas clowning around as a youngster at a wedding, another had been taken when he was slightly older and on a bear hunting trip in Pocahontas County. More recent shots included his graduation photo and one where he’d been a 22-year-old running a grader during construction at the Macy’s site – just one year before he died.

As he began to speak, Copenhaver readily acknowledged how hard it is to comprehend the hell his son – and entire family – faced due to addiction.

“The governor has asked me to talk to you about my personal experiences in the Copenhaver family, as well as how Berkeley County Council is moving forward. These are pictures of my wonderful son,” he said with a nod to Gov. Earl Ray Tomblin, then pausing to take a deep breath before he could continue to speak.

“I’m the only one standing here in front of you today, but I know Douglas is going to tap me on the shoulder when I lose my composure,” Copenhaver said, recalling carefree childhood days with his “perfect, kind and very loving son” before alcohol, marijuana and prescription pills entered the picture.

Gesturing toward a picture taken in high school, Copenhaver said, “Even in his graduation photo, you can look into his eyes and see how innocent he is.”

But as he got a little older, the trouble began.

Ironically, his son first learned about opioids when he went to a treatment center in Winchester for his alcohol problem, Copenhaver said.

Conquering his drug addiction wasn’t possible for Douglas, who couldn’t stand to go back to jail -and that only made him self-medicate more, Copenhaver said, before beginning to describe the traffic stop that preceded his son’s Aug. 5, 2011, death.

At that time, Douglas couldn’t stand the thought of once again disappointing his family by being incarcerated again, so he drove his vehicle into a steel pole and died as a result of his injuries, Copenhaver said.

Since he died from a vehicular accident, Douglas’ death was not officially considered to be drug related and that’s a shame, since many others have also died – indirectly as the result of drug addiction – but aren’t reflected in the local overdose fatality numbers, he said.

Perhaps, there will be soon be a treatment facility to help others like his son, Copenhaver said, referring to the council’s plans to help establish this kind of center locally. He also stressed the need to find alternative treatment other than jail for drug addicts – a plan that could save the county roughly $3 million annually in regional jail fees.

Not unlike others who teared up listening to his story, Tomblin was clearly emotional as well, and so choked up that it took a minute before he could thank Copenhaver.

“That’s tough,” he said softly, shaking his head.

“And it’s just so sad, but I do want to thank you for all that is being done by the council. I think you are exactly right that we cannot continue to incarcerate – we’ve got to get people the help they need,” Tomblin said.

KNOWLES: SOBRIETY IS POSSIBLE, BUT NOT EASY

Knowles readily acknowledged that he’d had it all before becoming an addict – a loving supportive family, good job and bright future.

“But take it from me, addiction is a taking disease, because soon your dreams and even your future is all gone,” he said.

Now in his 18th year of recovery, Knowles said his problems began with alcohol but also included cocaine in the 1980s.

While Knowles never thought he could ever get hooked on drugs, it only took one time with cocaine and everything changed, he said.

“I snorted the drug I was offered, and the first thing out of my mouth was, ‘Where do I get more of this?'” Knowles said.

At that time, he was living two lives – an addict and a successful high school sports coach.

Time spent at a treatment center allowed him to kick cocaine, but his downward spiral into alcoholism continued and eventually cost him his family because alcohol was the priority, Knowles said.

After quitting for a while, Knowles said he made a choice to “leave sobriety” after the death of his father, who was also his best friend.

He said his “last bout with active addiction” was in October 1997 and was so bad that it left him no choice but to change.

Not that it was easy, especially when it came to repairing relationships that had been neglected when he was drinking.

Choking up, Knowles still vividly recalled having been given a quarter to use a pay phone to call his 20-year-old daughter so he could apologize for having missed so much of her life.

“When I heard her voice on the phone, I began to apologize and I was crying like a baby,” Knowles said.

She had some good advice, he said.

“She said I needed to bring God back into my life, and she was right,” Knowles said.

In addition to moving to Berkeley County 11 years ago, Knowles actively works to help others overcome addiction and has seen “people die right and left” in the process.

Locally, the problem is that there’s no place to take an individual after an intervention was held in a family member’s kitchen or living room, he said.

“There’s nowhere to take them, there was no insurance and most of them died right after that,” Knowles said.

While admitting to being scared before the program began, Knowles finished his presentation by talking about the peace that had come over him as he spoke.

“Hope is here today, hope is here in this room,” Knowles said.

“This is about saving lives in Berkeley County,” he said.

Staff writer Jenni Vincent can be reached at 304-263-8931, ext. 131, or www.twitter.com/jennivincentwv.